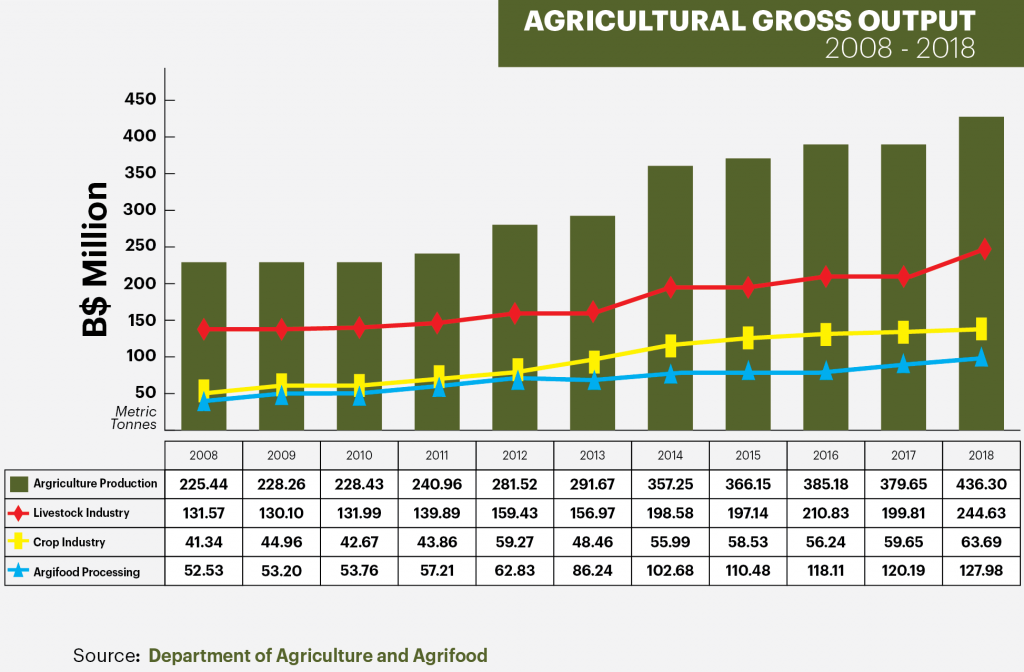

Unadjusted for inflation, Brunei’s gross agricultural output reached an all-time high of $436.30 million last year. The largest gain was seen in the livestock industry, driven largely by the poultry sector, which is now able to fully meet local demand.

Despite record growth, the industry’s overall contribution to national GDP remains minor at just 0.54% – the lowest in ASEAN outside Singapore.

Imports still make up 53% of the vegetables, 63% fruits and over 90% of rice in the local market, while local supply of cattle and sheep meets 29% of demand.

The Ministry of Primary Resources and Tourism (MPRT) previously set an ambitious target for the industry to grow at a rate of 24% annually, reaching $1 billion by 2020.

Nine initiatives – from affordable farmland to market access – are currently in place to boost productivity. But it’s the Brunei Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) – a national certification that’s yet to receive much public attention – that could usher in a new era of quality management amongst farms nationwide, and ultimately provide some answers to how Brunei’s crops can go international.

Since its introduction in 2014, uptake to Brunei GAP has been slow. By 2017, only three businesses had attained the certification: Hua Ho Agricultural Farm, Bioprop Farm and EcoNadi Agrobiz Farm.

Last week, after Moncherry Fruit Farms and Gropoint became the latest additions, the Brunei GAP Secretariat – headed by the director of the Department of Agriculture and Agrifood (DAA) under MPRT – announced that the certification was now a requirement for farms operating within the government-owned Agriculture Development Areas (KKP).

With an uphill task of getting several thousands of farms certified, DAA has struck up a partnership with local startup Zeneco Solutions, who claims to have a solution to onboard Brunei’s smallholder farms rapidly, with the help of their mobile application Agrome IQ.

Managing your farm – and Brunei GAP – through your mobile?

Brunei’s GAP follows the introduction of the ASEAN GAP in 2006, which is based on the Global G.A.P, the world’s most widely implemented farm certification scheme.

The Global version offers 16 different standards across crops, aquaculture and livestock, but they share the common principle of setting food safety requirements for a farm’s output while minimising the detrimental environmental impacts from its operations.

The ASEAN GAP currently applies to fruits and vegetables and covers four modules in food safety, product quality, environmental safety and workers’ health, safety and welfare. Brunei’s version focuses on food safety and product quality, which the secretariat views as the most demanded by distributors and customers.

There’s no digital requirement for GAP, but record-keeping is essential, and Zeneco and Agrome’s founder Dr. Vanessa Teo believes their mobile application provides the simplest, most affordable and efficient method to do so.

“Most smallholder farms (below one hectare) lack the (administrative) resources to be able to document their operations or deploy task management systems for their farms,” said Teo, whose company is the first to be endorsed to conduct GAP training and consulting in Brunei. “From research (on farms in Brunei) we’ve found that many still operate based on memory.”

The Agrome application – currently free and available for Android in English and Malay – is a farm management software, where daily farm tasks are assigned and tracked by managers and their farmhands.

The GAP’s required record-keeping, previously in the form of a physical booklet, has been integrated into the app. By documenting what goes into each planting cycle through tasks, farmers will also be able to trace back a season’s productivity through the app.

Zeneco, the subsidiary of Agrome, will be training Brunei’s farms to use the application and visiting farmers in person to consult them on any measures they need to take to get their farms GAP certified. The introductory price for the training and consultation is $200.

“Having all or the majority of (commercial) farms GAP certified can be a game-changer for Brunei,” said Teo. “Right now (in the short-term) we are looking at engaging 1,000 local farms within KKP that are the most ready for certification.

“By meeting good practices, the quality and amount of yield of farms will also increase, and combined with the branding (of GAP) our farmers will be able to export more competitively with better prices.”

100,000 farms in two years

In June, Teo marked another milestone by signing a memorandum of understanding with national agencies from the Brunei Darussalam-Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA).

The agreement, titled Digitalisation of Smallholder Farms, acts as a national endorsement for Agrome to work with local partners in the four signing countries to roll out their application.

“Through this MoU, I believe we can onboard 100,000 farms in two years,” said Teo. “From this we will be able to generate a massive data set which we can use to take Agrome into new directions of agricultural forecasting, modelling and artificial intelligence.”

Earlier in May, following their second six-figure (over $100,000) investment, Agrome announced their new, Singapore-based CTO Michael Knott, who has over 20 years experience in Fintech.

“A lot of startups in the agritech space are focused on developing and researching new farming methods using the latest technologies, and while there is a need for that, there are not many who are looking at solutions that can be immediately adopted by the majority (of traditional farmers) that are currently operating in Southeast Asia to improve their livelihoods,” said Knott.

“That’s what draws me to Agrome. They are approaching things from the smallholder farms point of view, who make up the majority, but who can’t afford to purchase the latest high-tech machinery or experiment with gadgetry. What we are looking at instead is what are the most cost-effective solutions that everyone can implement to improve their yield.

“I agree with Vanessa, that it starts off with the basic record keeping and getting GAP certification. From there we can gather data on how farms are operated, and develop the app to be able to give farmers feedback and recommendations to improve productivity.”

To stay profitable, Teo plans to monetize Agrome with a monthly subscription fee. Aside from offering farmers recommendation, the platform’s next step will be creating an online community that connects its farmers together to make group purchases and supply.

“Through the community, farmers will be able to make bulk purchases together for items such as fertilizer and equipment and also supply as a group to new markets,” said Teo. “We have 50 potential restaurants from Singapore who are already interested in buying produce from farmers on Agrome.”

Digitalisation: a foregone conclusion?

Teo is in many ways the archetype of a digital native. The petite 30-year-old is a graduate from UBD’s IBM centre with PhD in High Performance Computing specializing in Rice Crop Modelling and Agricultural Systems Management.

She holds undergraduate and master’s degrees in science from Imperial College London, and immediately after submitting her PhD thesis, flew to Canada to spend 12 weeks in a web coding bootcamp by Lighthouse Labs to develop the first prototype of Agrome, then known as FarmNotes.

“Growing up I always wanted to be in the fields of research and education,” said Teo, who was inspired by her elder brother of 10 years Mikhail Gregory Teo, who works as a science teacher.

“But doing my PhD is when it started to change. I realized the limited impact my research would (ultimately) have if it wasn’t made into something farmers could easily use. When I had handed in my thesis, I was relieved, but at the same time I knew my work had just begun.”

After returning to Brunei in 2016, Teo – then trying to market her app on her own – had a chance run-in at iCentre with DARe’s then CEO Soon Loo, an award-winning Bruneian entrepreneur and Harvard Business School graduate.

“I quickly showed him what I had built on my laptop,” recalls Teo. “He replied: ‘You’re joining our DARe bootcamp.’ That’s where it all began for me.”

The broad, sweeping narrative of digitalisation stipulates that those who don’t participate will be left behind. For Agrome, this is especially true. The degree to which they succeed ultimately depends on how much they can influence smallholder farms to wholeheartedly embrace their service.

“Agrome has to make sense to them; not only must it be easy to use but it must be really adding value to their operation if we want them to continue using it every day,” said Teo.

Brunei – similar to other countries who are overly reliant on food imports – continue to be vulnerable to fluctuations in supply and prices. Factor in global forces such as population growth, scarcity of resources and climate change, and it becomes apparent that Brunei must set out to secure its own food security.

“I have stressed that agriculture is an area that determines our survival as an independent people and nation,” said His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah in his address at last year’s Knowledge Convention. “There cannot be any more excuses for us slowing down in agriculture.”