It’s the middle of February and Wasan –

Overlooking his lots of five hectares, Hj Mohd Sahlan Hj Hidup, chairperson of Koperasi Setia Kawan (KOSEKA) – Wasan’s largest tenant and Brunei’s biggest rice producer – is quietly confident that they will yield their largest harvest yet.

“This is our first harvest of Sembada(188),” says the 60-year-old of the new hybrid rice strain. Jointly developed by Indonesia’s Biogene Plantation and Brunei’s Department of Agriculture and Agrifood (DAA), Sembada is being commercially piloted over 38 hectares and along with another hybrid titith, are being touted to usher in new levels of productivity to Brunei’s rice fields that will hopefully drive the nation’s ambitions of self-sufficiency.

“Some are reporting yields (from Sembada) high as five to six (tonnes). That’s nearly double Laila and MRQ76.”

Today, Wasan is known as the heart of the Sultanate’s rice production, but few know that the project dates back to 1978 when it debuted as Brunei’s first large scale, mechanized rice planting experiment.

Fewer know that it failed to take off initially, reverting to a bush-like state after being abandoned, and that it was Hj Mohd Sahlan – a retired Lieutenant Colonel – who marshaled a bastion of retired military members to answer His Majesty the Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei Darussalam’s call for food security by reviving it in 2006.

Declining rice self-sufficiency: agrarian to industrial

Four years before the Wasan Rice Project (WRP) began, Brunei’s self-sufficiency in rice was entering a state of free fall. According to DAA statistics, local supply met 37.5% of the rice consumed in 1974, dropping to 13.7% by 1978.

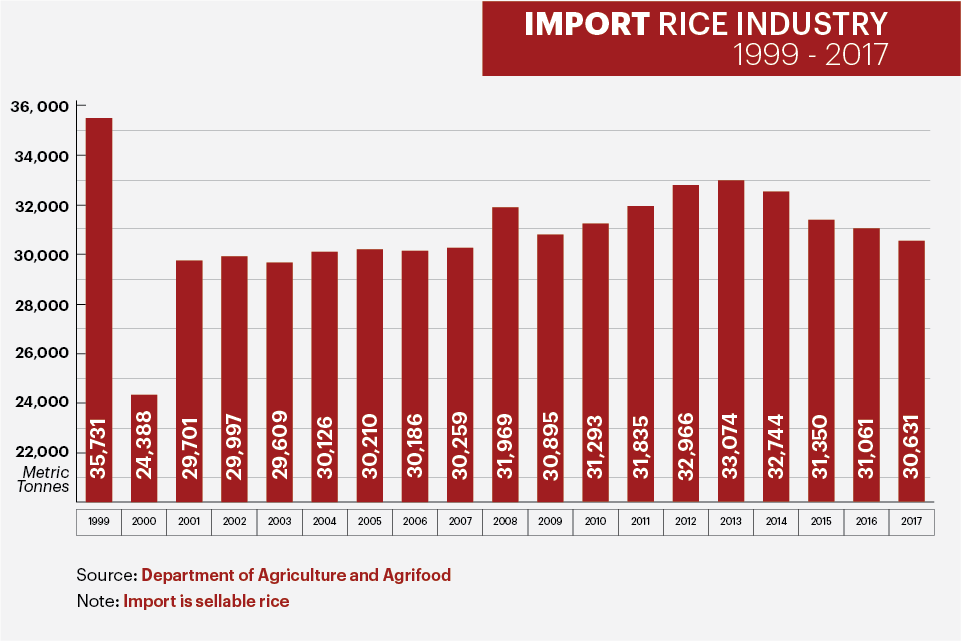

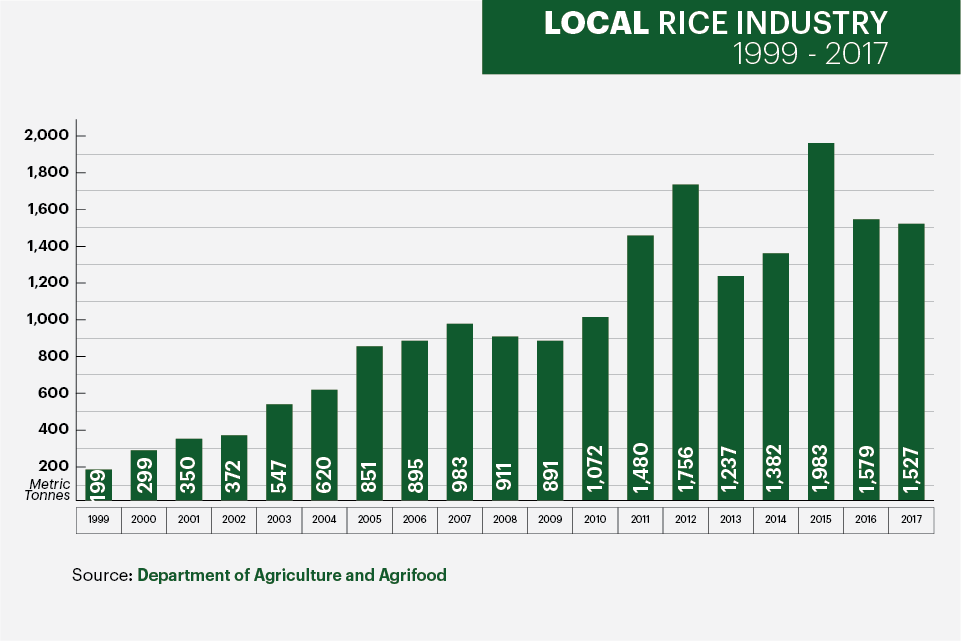

Imports filled the gap, and rose in tandem as the population increased. Today, Brunei imports around 30,000 tonnes of rice annually, triple the amount it imported in 1974 – but produced just 1,527 tonnes of rice in 2017, compared to 6,348 tonnes in 1974.

In an

“Although (the) government spent millions of dollars on agriculture, this industry had lost its appeal,” writes Khairunnisa on the prevailing sentiment of the 1970s. “Gradually, the number of farmers working on the rice fields decreased and plots of land were abandoned.”

Around the same time,

Issues over management and the surrounding environment, coupled with gaps in technical know-how and infrastructure, plagued the project from the outset. Annual output peaked at 282 tonnes in the eighth year, but the project was far from meeting expectations. The government then decided to privatize WRP with foreign joint ventures, none which succeeded.

No official records are readily available online on what happened to Wasan after this period. Not until

Hj Sahlan comes full circle

Hj Sahlan’s earliest memories of his father were of

Any surplus was sold or traded in the market for fish, maybe some meat if they were lucky. Looking to provide a better life for his family, Hj Sahlan enlisted as a soldier with the Royal Brunei Land Forces in 1968, and by 1994, was bestowed an epistle from His Majesty to serve as the third battalion’s first commanding officer.

When Hj Sahlan retired in 2000, he needed a new cause; whittling away his pension unproductively was not of interest. Staying abreast on national issues – particularly the nation’s lagging agricultural industry – he decided to join the Village Consultative Council (MPK) of Bebluloh’s rice project near his home, farming traditional varieties like

Here, he would learn first hand, what some scholars have gone on to argue; that rice farming is more laborious, and arguably more complex than growing any other staple crop.

On average, wetland rice cultivation takes at least double the steps wheat requires. Writing about the work ethic needed to cultivate rice successfully, Malcolm Gladwell describes that each field must be irrigated, with series of dikes constructed and channels dug near the water source, which must then have inbuilt controls to allow precise inflow of water.

The soil has to be repeatedly fertilized and have a hard clay floor to prevent water from seeping into the ground, yet have a softer layer atop so seedlings can stay submerged at the right moisture level.

Farmers must then select carefully their paddy variety to plant, each which carries their own trade-off; between yield and maturity time or moisture and soil composition. Seedlings are also grown separately before being transplanted onto the farm. Daily inspection for weeds, pests

“The truth is rice is cheap (in Southeast Asia) but it’s challenging to farm,” said Hj Sahlan. His blanket assertion has

“When I first approached them (the authorities) I think they didn’t think I was serious,” jokes Hj Sahlan. “But I told them that we had 200 (ex-military) on standby, willing to get into this full-time. His Majesty in his

The revival of Wasan

With the government’s green light, Hj Sahlan formed a cooperative to unify their efforts, and they began clearing Wasan once more.

Structurally, KOSEKA was very different from a traditional cooperative, or a private company for that matter. Operationally, it acted more as an association that would centralize the sale of farmers’ paddy harvest to the government, and

By the same token, KOSEKA as a collective would not invest individually in any one lot – it was up to the members themselves to manage their own parcel of land, decide how much they wanted to farm, and what capital they would front to kickstart their operations.

Essentially, KOSEKA’s members were their own self-contained micro-businesses, responsible for their own profits and losses. At first glance, the approach seems harsh, but Hj Sahlan insists the opposite was true.

“It created a sense of belonging (between member and the farm),” he said. “It (KOSEKA) is not a cooperative or company where you have investors (shareholders) who put in money and entrust an administration who then hire and operate the business and then give you dividends (or profits) at the end of the year. You don’t have a sense of ownership or relatability this way to the struggle of the farm. You have to be the one operating it.”

The founding members quickly established

The government laid out an extensive subsidy framework which remains in place today; seeds, basic equipment, fertilizers and pesticides were discounted by at least 50%, and famers’ paddy would be bought back at $1.60 per kilogramme. Agriculture authorities also built the Imang Dam nearby with a reservoir of 10 million cubic metres of water and opened a rice milling facility that would also package the farmers’ rice and supply to retail stores nationwide.

By KOSEKA’s estimations, each hectare would need to yield at least 1.6 tonnes a season to break even. At two tonnes, they would make just a $700 profit, a poor return for six months of operations.

“At the start, it was very difficult,” said Hj Sahlan. “Many members left because they realized that the costs were too big up front. Others left after a few seasons realizing that the margins were too small to sustain.”

The remaining 80 plus farmers toiled 186 hectares, each employing one to four Indonesians. Shortly after, MPK Pengkalan Batu entered the fray, creating a somewhat contentious situation according to Khairunissa’s study, but they eventually settled on taking up the remaining third of Wasan.

Results for both parties came slow, but those that persisted had their first big win in 2009 when DAA unveiled Brunei’s first hybrid variety Laila, capable of three tonnes per hectare.

His Majesty arrived in Wasan to officiate both the planting and harvest, underscoring rice planting as a national priority. The then Ministry of Industry and Primary Resources proceeded to set an ambitious target of 60% self-sufficiency by 2015, to be achieved by opening up 10,000 hectares for rice farming across Brunei.

KOSEKA followed through with their first annual revenue over a $1 million in 2011, surpassing it the following year with $1.87 million as they became Brunei’s largest rice producer.

It appeared to be a watershed period for Brunei’s rice industry, signaling a new era for Brunei agriculture. But the target was never met. In 2015, rice self-sufficiency stood at just 4%.

An unfufilled promise

Taking a more measured approach, new Minister of Primary Resources and Tourism (MPRT) Yang Berhormat Dato Seri Setia Hj Ali Apong said at last year’s Legislative Council session that the government would be targeting a 20% self-sufficiency in rice by 2020, and had set aside $45 million for rice and vegetable cultivation.

Last November, His Majesty said that there could be “no more excuses” for the nation to not progress in agriculture, announcing a new 500-hectare rice field in Kandol, Belait that once operational, would take the mantle as Brunei’s biggest rice farm.

DAA says Kandol is less likely to face the same soil acidity issue, with the land made up of a finer-grained fertile soil which carries alluvial sediment deposited from water flooding over.

Back at Wasan, founding members of KOSEKA Hj Mohd Zain Abd Ghani and Hj Mohd Saifulizan Hj Mohd Alishah drop by Hj Sahlan’s farm. With His Majesty visiting just a few days ago to harvest Sembada, they’re in good spirits, welcoming DAA’s plans to increase the

Hj Sahlan points out that His Majesty is not just calling for food security, but for agriculture to contribute to the economy. He then initiates a controversial topic amongst the farming community – weaning off government subsidies.

Some feel that the government hasn’t done enough over the years, especially in following through on plans promptly and in their upkeep of infrastructure, most critically over the supply of water.

In Belait, the unirrigated 300-hectare Sengkuang – at one point Brunei’s largest rice farm and the district’s rice bowl – is now a shadow of its former self after losing its ability to flood from naturally from a nearby river. According to DAA, groundwater wells will be trialed soon.

Over in Wasan, it’s common for farmers to take turns using the water from Imang Dam, because they claim the pressure isn’t enough for simultaneous use. A senior DAA official mentioned this week that the dam hasn’t been maintained since it was completed in the late 1990s.

Hj Sahlan cuts through the arguments, claiming that if it weren’t for the subsidy framework, farming rice wouldn’t have taken off in the first place.

“Yes, the authorities must maintain the infrastructure, follow through on plans and keep us updated.

Whatever paddy farmers can produce, the government will buy at $1.60/kg. After milling, 1,000kg of dried paddy yields approximately 650kg of rice. The government then packages it and sells the rice at $1.15/kg to retail stores to stay competitive against imported rice, which is also subsidized.

“This means the government is buying rice from us at $1.60 for 650

“The truth is that while we are contributing to food security, we are not contributing back to the economy; we are costing the government money. KOSEKA’s long-term future must be being profitable (without subsidies) for us to truly answer His Majesty’s call.”

As a start, Hj Sahlan estimates that farmers must yield at least six tonnes per hectare, every season, as a minimum, to be profitable without the

“The new hybrids (we’re told) have the potential to yield a minimum of six tonnes,” says Hj Sahlan. Titih, another hybrid being jointly developed by DAA with a Myanmar firm, is reportedly able to yield eight tonnes and is soon due to be trialed commercially. At Wasan, Hj Sahlan says the soil acidity is now manageable after repeated fertilization. If the

In 2017, KOSEKA accounted for over 40% of all rice produced in Brunei, and on paper, their produce of 1,069 tonnes from 186 hectares equates to a yield of 2.87 tonnes per hectare, more than double the national average of just over one tonne per hectare.

Hj Sahlan and his founding members are proud of all their milestones, and will certainly feature in any study or historical account of Brunei’s journey in rice farming.

But there’s also a sense of urgency to do more. For all the mechanization and modernization, Brunei still produces four times less rice than it did in 1974.

Watch: KOSEKA’s journey to becoming Brunei’s biggest rice producer

![[Video] Brunei’s economic diversification journey under Wawasan 2035 Second MOFE Minister YB Dato Amin explains Brunei's divesrificaiton strategy.](https://www.bizbrunei.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Bruneis-future-vision-Wawasan-2035-Thumbnail-100x70.jpg)