It’s referred to as anti-trust laws in the United States, anti-monopoly laws in China and trade practices law in the UK. However, the rationale behind competition regulations are fairly consistent – they seek to ensure fair trade for businesses and protect consumer welfare.

In Brunei, competition regulations came with the introduction of the Competition Order in 2015 – although it is still working towards enforcing it.

130 countries across the world already enforce competition laws and within ASEAN, only Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Brunei have yet to enforce it.

So what does Brunei’s Competition Order cover, and why does it need it?

Prohibiting against three main harms

In roadshows and dialogues with the business community, the Economic Planning and Development Department (JPKE) at the Prime Minsiter’s Office who have largely overseen the conceptualizing and delivery of the order, have summarized prohibited activities into three key practices.

The first are anti-competitive agreements, which can lead to cartels. Acting Director of the Competition and Consumer Affairs Department in JPKE Heidi Farah Sia Rahman said that these include price fixing, fixing market share, controlling supply and rigging bids.

Price fixing is banding together with other companies or through some form of association to set high prices and restrict competition, while fixing a market share means dividing the market – whether geographic or demographic – for the purpose of allowing a company to exclusively dominate or monopolize that market.

“An example is that companies agree amongst themselves that one will only cater to the Brunei-Muara market while the other will only cater to Tutong,” said Farah.

Purposefully restricting the supply to raise prices is also against the order while bid rigging – where companies conspire to share information illegally amongst themselves to increase or control the tender price – is also against the law. Anti-competitive agreements will the be the first regulations of the order to be enforced.

The second is the abuse of dominant positions. Dominating a market isn’t illegal – but abusing a dominant position is. This is where an enterprise uses its leading position in an exclusionary or exploitative manner to earn favourable outcomes that it would not have been able to secure in open competition.

The third category of prohibitions are anti-competitive mergers. Again, mergers themselves – where two enterprises combine to form a single, larger company – aren’t illegal. However, the merger is illegal if it leads to anti-competitive behaviour such as a direct increase in prices, lower quality and restricted number of options for consumers.

What organizations does the order apply to?

All commercial entities or enterprises – including government-linked companies (GLCs). However, JPKE clarified that it doesn’t apply to government or statutory bodies.

What are the penalties and consequences for not complying?

The two most direct penalties under the order are a 10 per cent fine of the business’ turnover for a maximum of three years and suspension of business activity. Consequences could also include being sued by third parties and losing business credibility or reputation.

Are there any exemptions?

There are automatic exemptions to the order, as well as grounds to apply for exemptions. In both, exemptions are either based off government policy and regulations or by weighing the overall cost-benefit of the practice for the Sultante’s socio-economy.

This means products or services sold at fixed prices or by only a set number of vendors are permissible if there is existing regulations or policy endorsing such practices. An example is the price ceiling on certain commodities (such as basic food times) done by JPKE in the interest of making sure these are available and affordable to the public.

When will the order be enforced?

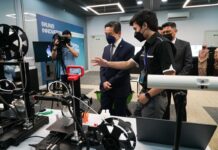

JPKE did not publicly disclose a timeline for the order’s enforcement but insisted that it would be in the near future. At a dialogue held yesterday with members of the business community at the Design and Technology building in Anggerek Desa, the Acting Director of the Competition and Consumer Affairs Department said that important milestones had been achieved towards implementation and that building the capacity for effective enforcement was underway.

“The Competition Commission was set up last August which is an important milestone in the enforcement framework,” said Farah. “The commission itself will judge over cases, but there will also be a tribunal for appeals.”

What’s the bottom line?

In the widest and most conceptual sense, the Competition Order is aimed at helping Brunei’s economy by ensuring a competitive ecosystem of open and efficient markets that improve consumer welfare.

“By having regulations against anti-competitive behaviour we ensure a market that’s fair and healthy,” said Farah. “This is will support the economy by ensuring that businesses remain productive, innovative and dynamic, in line with our national vision Wawasan Brunei 2035.”

In the short-term, having competition regulations also allows Brunei to meet the requirements of several free trade agreements it is actively pursuing, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

To learn more about the Competition Order visit JPKE’s website. To view the full text of the order click here.